Market snapshot

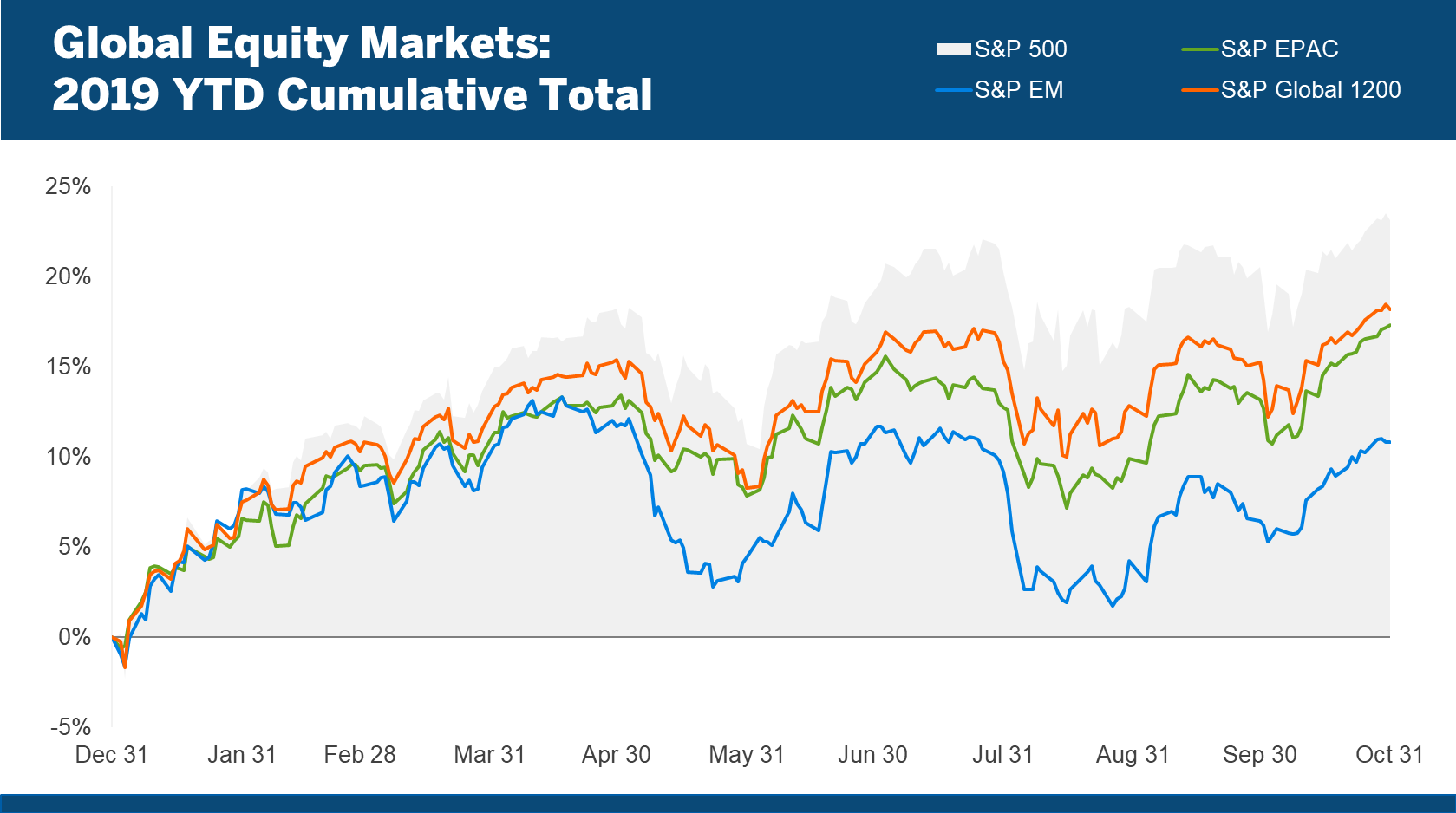

The global equity market in October notched its second consecutive monthly return of more than 2% and its eighth positive monthly return for 2019:

Since touching its 2018 low on December 24, the S&P Global 1200 Index has generated a total return of 26.3% through the end of October. That strong return notwithstanding, the index finished the month still just shy of the all-time it hit in January 2018.

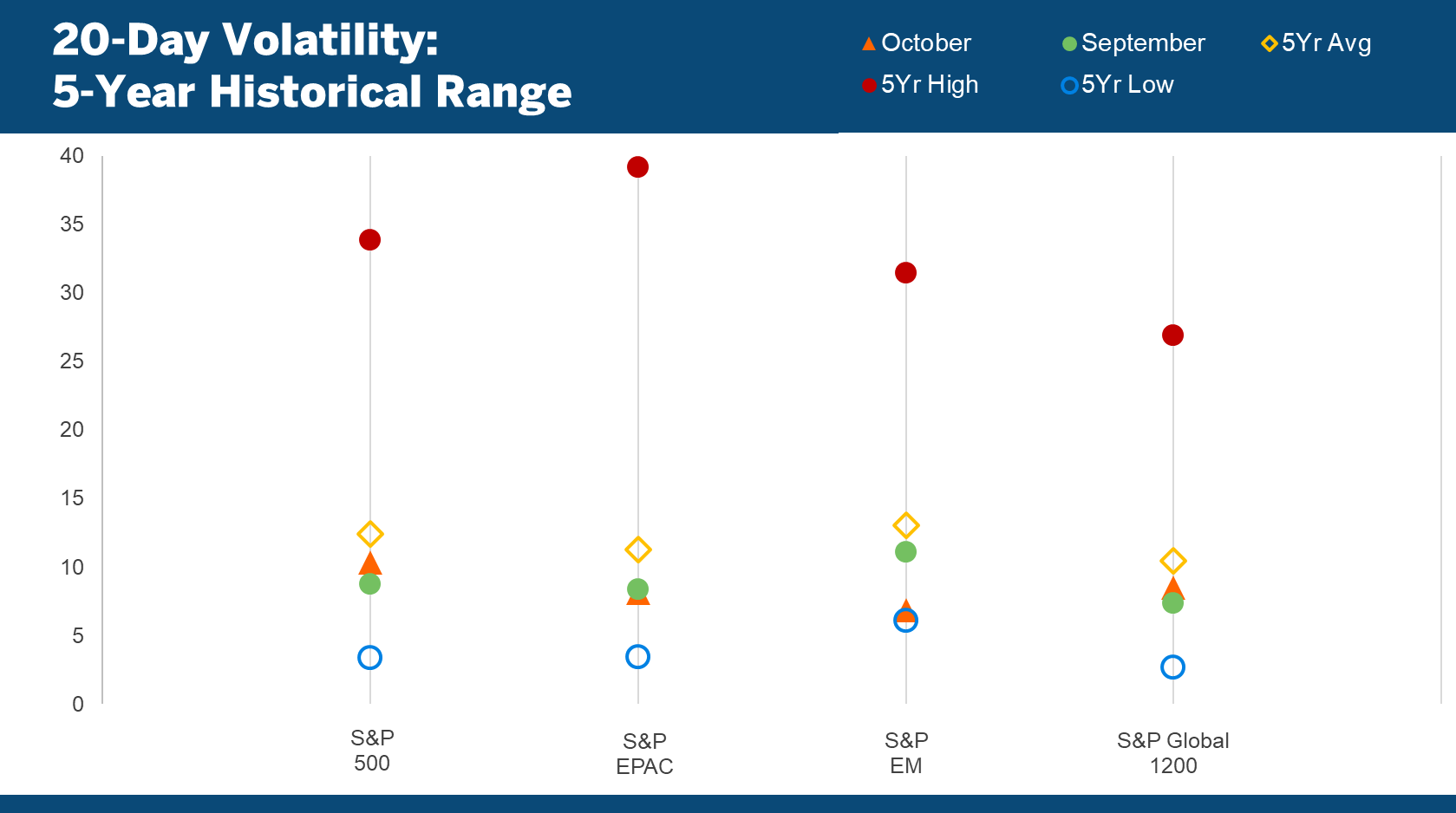

Volatility

Equity market volatility around the globe was largely unchanged from the previous month, with the exception of emerging market volatility, which was about two-thirds of what it was a month earlier:

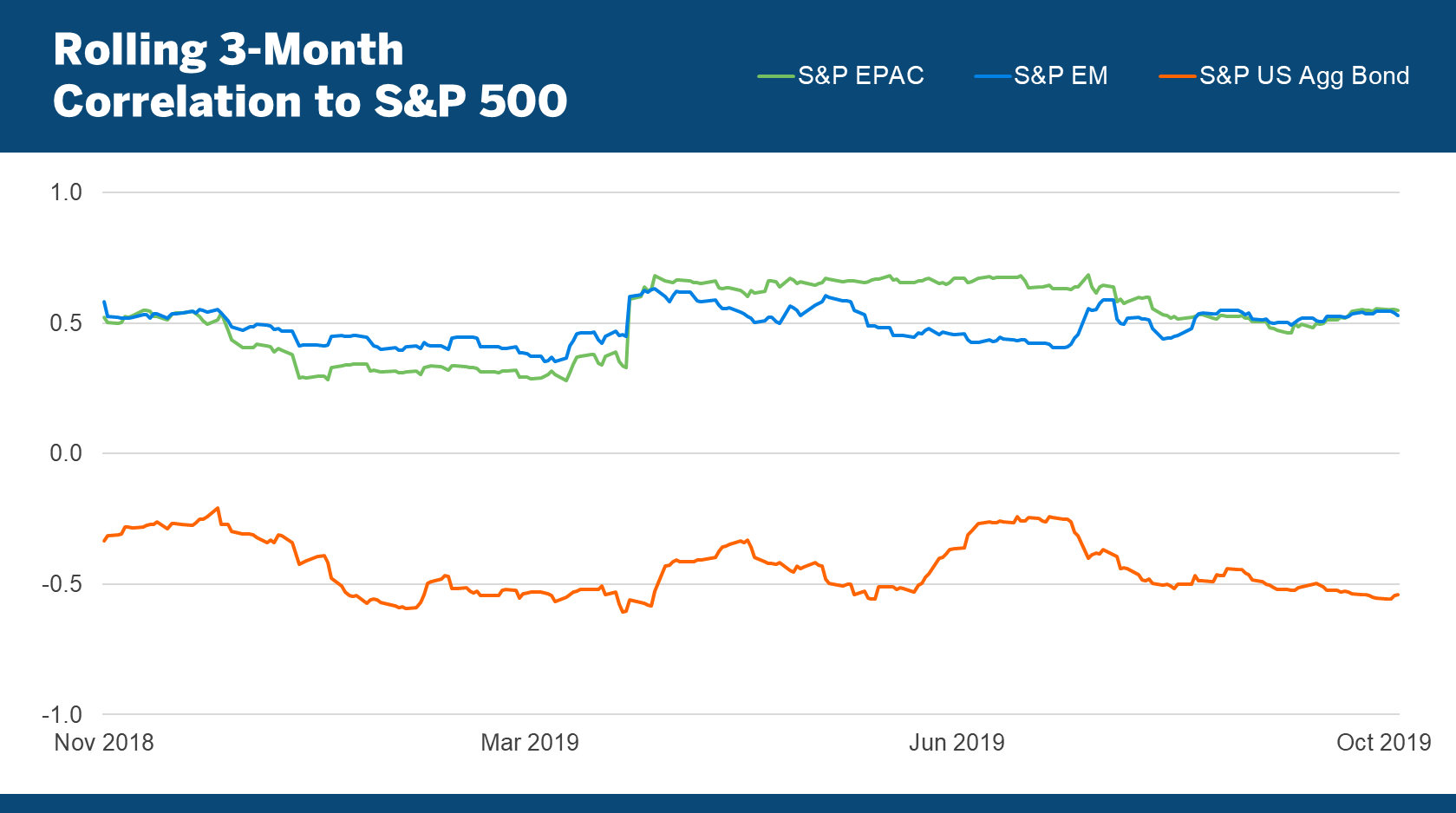

Correlations

The correlation of the S&P 500 to both international equity markets and to the US bond market remained remarkably stable in October, hovering around their longer-term averages:

Asset Class Returns

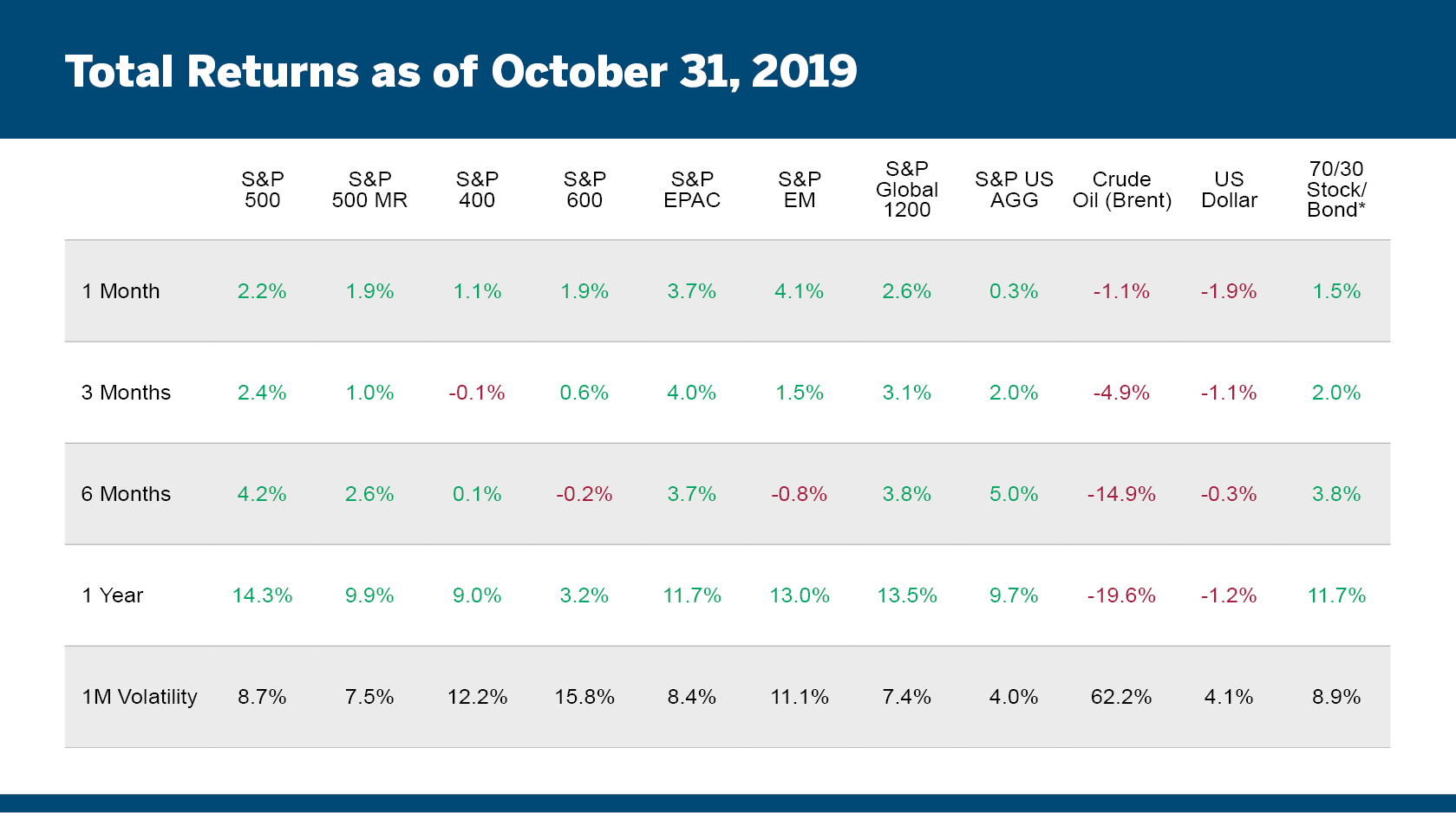

Much like last month, equity markets moved higher across all major segments, with international stocks leading the way:

There have only been three years out of the last 30 when the return of the S&P 500 was higher through the first 10 calendar months than it is in 2019. While all sectors have made a positive year-to-date contribution, no sector has contributed more to the index’s return than information technology. In addition to being the sector with the largest weight, IT also has generated the highest return (36.5%), contributing more than 2x the return of the next largest contributor (financials).

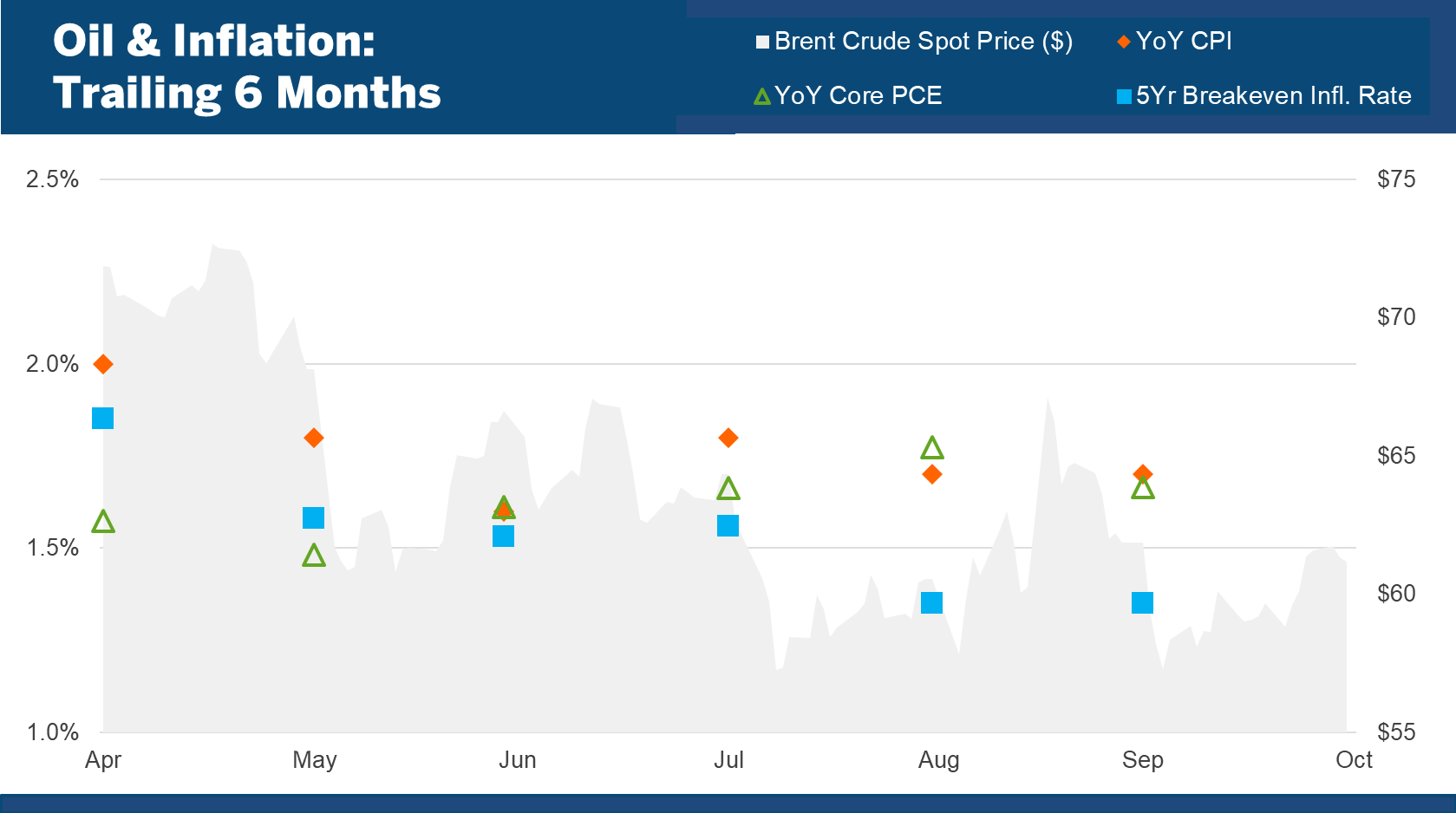

Inflation

The most recent inflation data showed that year-over-year personal consumption expenditure (PCE) edged lower while year-over-year CPI remained unchanged from the previous month. Five-year inflation expectations touched their 2019 low of 1.24% on October 9 before reverting sharply higher to 1.44% by month end.

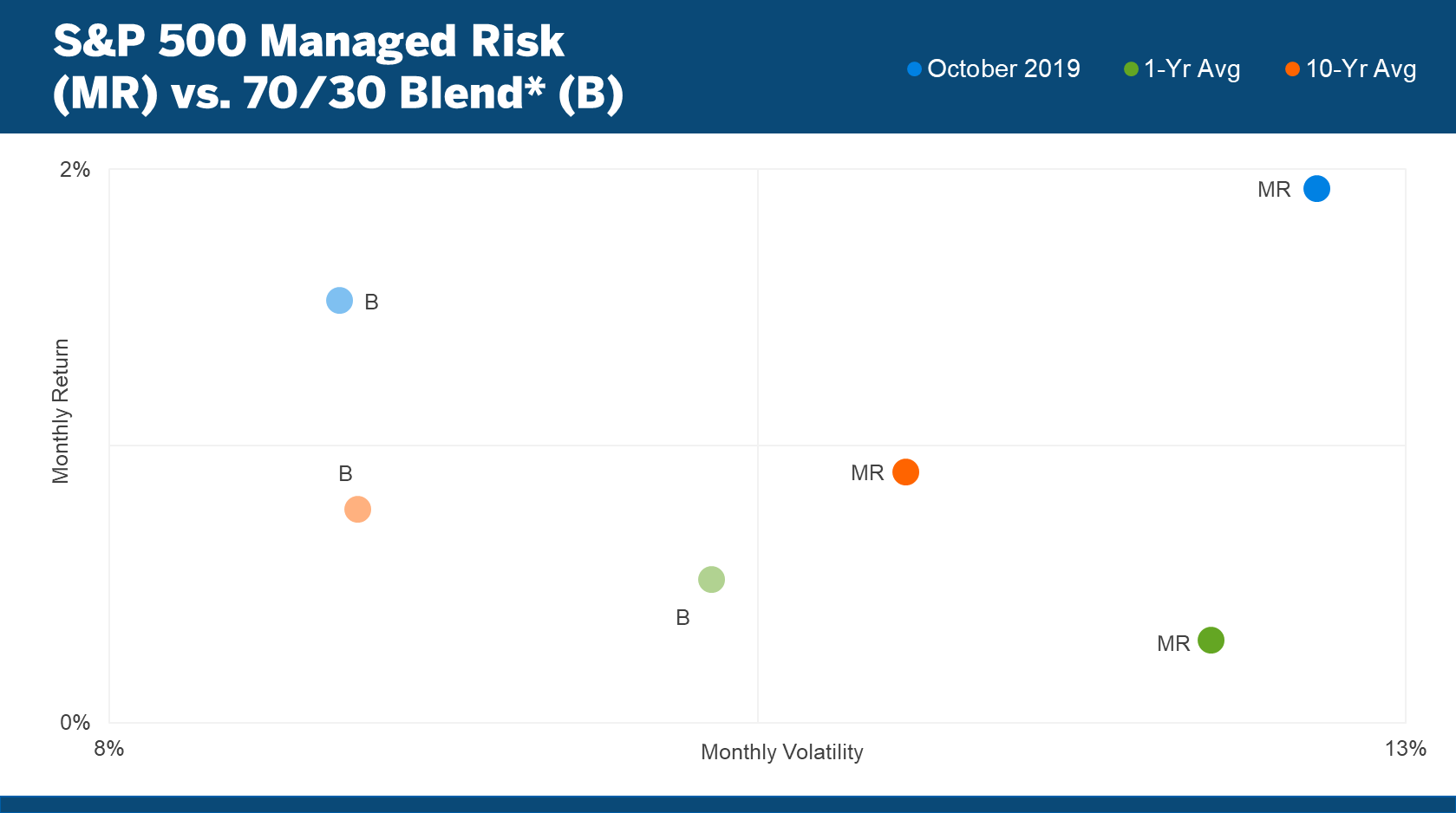

Managed Risk Investing

The volatility of the S&P 500 began the month below the 18% volatility threshold of the S&P 500 Managed Risk Index, but gradually climbed through mid-month, causing the index to reduce its equity exposure from 100% down to 93%. As the month wore on, volatility waned and the S&P 500 MR Index increased its equity exposure back to 100% for the last nine days of the month.

The Managed Risk Index outperformed a 70/30 stock/bond blend by 40 bps in October, but exhibited more volatility. Over the past year, amidst sharply falling interest rates, the 70/30 blend has generated an average monthly return that is 21 bps higher than that of the Managed Risk Index. Over the 10 year period, however, the average monthly return of the MR Index has outpaced that of the blend by an average of 13 bps per month.

Balance sheet expansion is not QE (and biking to work is not exercise).

At a conference for the National Association for Business Economics (NABE) on October 8, Fed Chairman Powell conveyed to attendees, “My colleagues and I will soon announce measures to add to the supply of reserves over time.” In the Q&A session that immediately followed, he asserted, “In no sense is this QE.”

Three days later on October 11 in its Statement Regarding Monetary Policy Implementation, the Fed formally communicated that in addition to carrying out repo operations at least through January 2020, it will also “purchase Treasury bills at least into the second quarter of next year...”

The statement was quick to note that these actions are “purely technical measures” and do not represent a change in the stance of monetary policy. That additional comment sheds some light on one aspect of Powell’s declaration that this is ‘not QE.’

When he says that it’s not QE, Powell is referring to the intent of the Treasury bill purchases and the resulting balance sheet expansion. He’s attempting to clarify that the Fed isn’t conducting these purchases for the purpose of making monetary policy more accommodative.

And yet, while it’s good and appropriate for him to clarify the intent behind the purchases, it’s largely irrelevant to the effect of the purchases. The Fed’s insistence that this is not QE is analogous to someone who begins biking to work after his car breaks down and insists that it’s not exercise because he’s only doing it for logistical reasons. His bike ride to work may not be for the purpose of getting exercise, but that has no bearing on whether or not he is actually getting exercise from it.

Similarly, the Fed may not be growing its balance sheet for the purpose of QE, but it doesn’t mean that balance sheet growth isn’t having the same effect as QE.

In some sense the Fed has already implicitly acknowledged the potential for this round of balance sheet expansion to have the same effects as previous rounds of QE. An October 11 press release from the Fed noted that,

"In particular, purchases of Treasury bills likely will have little if any effect on longer-term interest rates, broader financial conditions, or the overall stance of monetary policy. As a result, these purchases should not have any meaningful effects on household and business spending decisions and the overall level of economic activity.”

Relative to notes and bonds, Treasury bills have the shortest maturities, generally less than one year. The Fed thinks that limiting their purchases to bills will not have the same effect that their purchases of Treasury notes and bonds had during previous rounds of QE.

In one sense this is true. Fed purchases of T-bills won’t directly push longer-term yields lower. By not purchasing notes and bonds, the Fed will not be directly generating downward pressure on the yields of those securities.

Demand for Treasury bills, however, does not exist in a vacuum apart from, and without affecting, demand for other Treasury securities. Indirectly, lower short-term rates will push other buyers of Treasury securities further out the curve in search of higher yields, which in turn will generate downward pressure on longer-term rates.

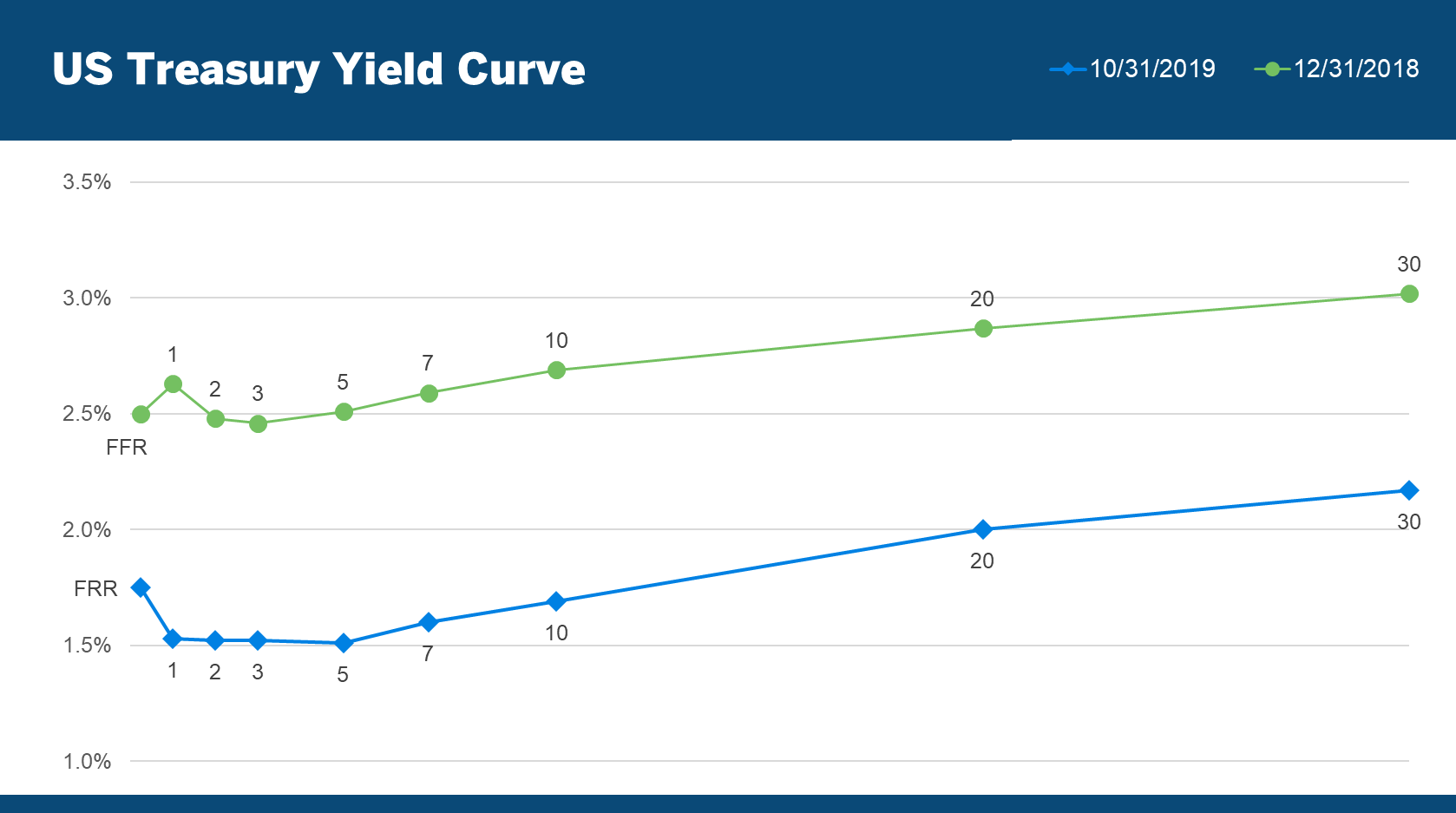

Another consequence of the Fed generating downward pressure on short-term rates is that it increases the likelihood of deeper curve inversion relative to the Fed funds rate. Even after the rate cut on October 30, the Fed funds rate (FFR) of 1.75% at month end was still higher than all the maturities on the curve up to 10 years:

To the extent that the last three rate cuts were in response to the yield curve’s inversion, these Treasury bill purchases may actually serve to increase the likelihood of additional rate cuts.

Unfortunately for the Fed, even in a world where virtue signaling is often given greater weight than virtuous conduct, the ‘not-QE’ declaration of intent cannot outweigh the real world effects of these purchases.

Interestingly (if not somewhat ironically), the press release goes on to say that these open market operations are “aimed at managing the level of reserves in the banking system.”

For an organization that has repeatedly said that management of reserve supply isn’t necessary in an abundant reserves regime, and that it doesn’t want to manage the amount of reserves in the banking system, the Fed seems to be inordinately focused on managing the supply of reserves.

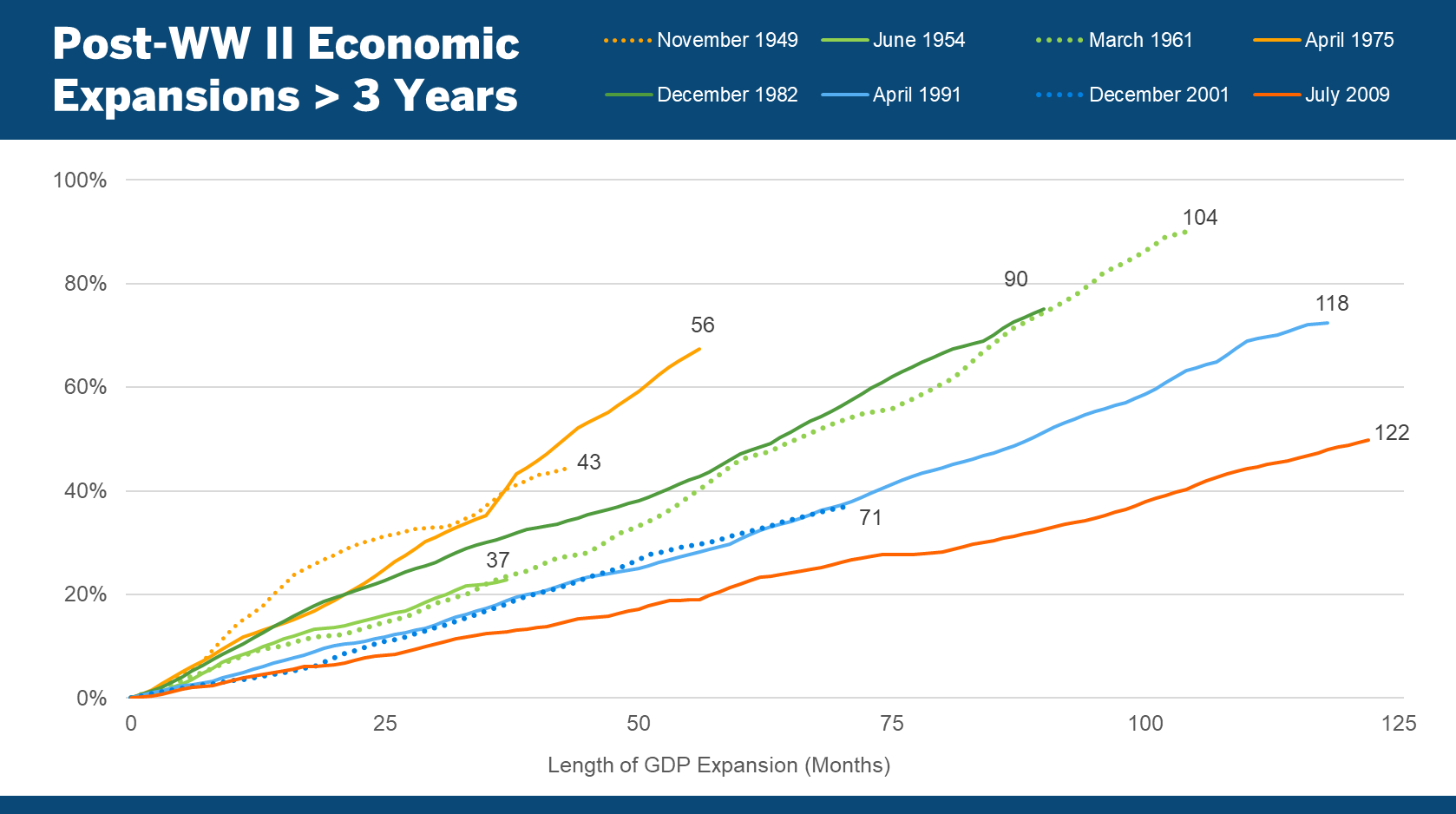

U.S. Economy Extends Its Winning Streak

The release of GDP data on October 30 indicated that the U.S. economy grew by 0.9% on a nominal basis in Q3, extending its current growth streak as the longest post-World War II economic expansion on record. 1 At 122 months, this expansion is more than double the 60-month post-WW II average:

In addition to the U.S. economy extending its growth record, the U.S. stock market also touched a new all-time high on October 30, as the S&P 500 surpassed its previous high set in July earlier this year.

Faced with these record-setting levels, one question that naturally comes to mind is, can this keep going?

Of course the simple answer to that question is yes, it can keep going. An expansion doesn’t have to end merely because of its length. In fact, the slower rate of growth of the current expansion relative to all the others may bode well for its continuation.

However, to the extent that expansions aren’t exempt from the norms of mean reversion, the longer this expansion goes, the greater the likelilhood that it will end. Given that observation, combined with the market’s new all-time high, the Fed’s diminished potency, and the potentially volatile political outcomes on the horizon in 2020, we believe the case for portfolio risk management is as strong as it's been in some time.

1Expansion is defined as GDP growth uninterrupted by recession. Recession is defined as two or more consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

*Measured by the S&P 500 and S&P US Aggregate Bond Index

The information, products, or services described or referenced herein are intended to be for informational purposes only. This material is not intended to be a recommendation, offer, solicitation or advertisement to buy or sell any securities, securities related product or service, or investment strategy, nor is it intended to be to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice.

The products or services described or referenced herein may not be suitable or appropriate for the recipient. Many of the products and services described or referenced herein involve significant risks, and the recipient should not make any decision or enter into any transaction unless the recipient has fully understood all such risks and has independently determined that such decisions or transactions are appropriate for the recipient. Investment involves risks. Any discussion of risks contained herein with respect to any product or service should not be considered to be a disclosure of all risks or a complete discussion of the risks involved.

The results shown are historical, for informational purposes only, not reflective of any investment, and do not guarantee future results. Any reference to a market index is included for illustrative purposes only, as it is not possible to directly invest in an index. Indices are unmanaged, hypothetical vehicles that serve as market indicators and do not account for the deduction of management fees or transaction costs generally associated with investable products, which otherwise have the effect of reducing the results of an actual investment portfolio.

The recipient should not construe any of the material contained herein as investment, hedging, trading, legal, regulatory, tax, accounting or other advice. The recipient should not act on any information in this document without consulting its investment, hedging, trading, legal, regulatory, tax, accounting and other advisors. Information herein has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable but neither Milliman Financial Risk Management LLC (“Milliman FRM”) nor its parents, subsidiaries or affiliates warrant its completeness or accuracy. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of facts obtained from third parties.

The materials in this document represent the opinion of the authors at the time of authorship; they may change, and are not representative of the views of Milliman FRM or its parents, subsidiaries, or affiliates. Milliman FRM does not certify the information, nor does it guarantee the accuracy and completeness of such information. Use of such information is voluntary and should not be relied upon unless an independent review of its accuracy and completeness has been performed. Materials may not be reproduced without the express consent of Milliman FRM. Milliman Financial Risk Management LLC is an SEC-registered investment advisor and subsidiary of Milliman, Inc.

The S&P Managed Risk Index Series is generated and published under agreements between S&P Dow Jones Indices and Milliman Financial Risk Management LLC.